“The good life is one that is motivated by love and steered by wisdom. An excellent life cannot be produced by either love or knowledge alone.”

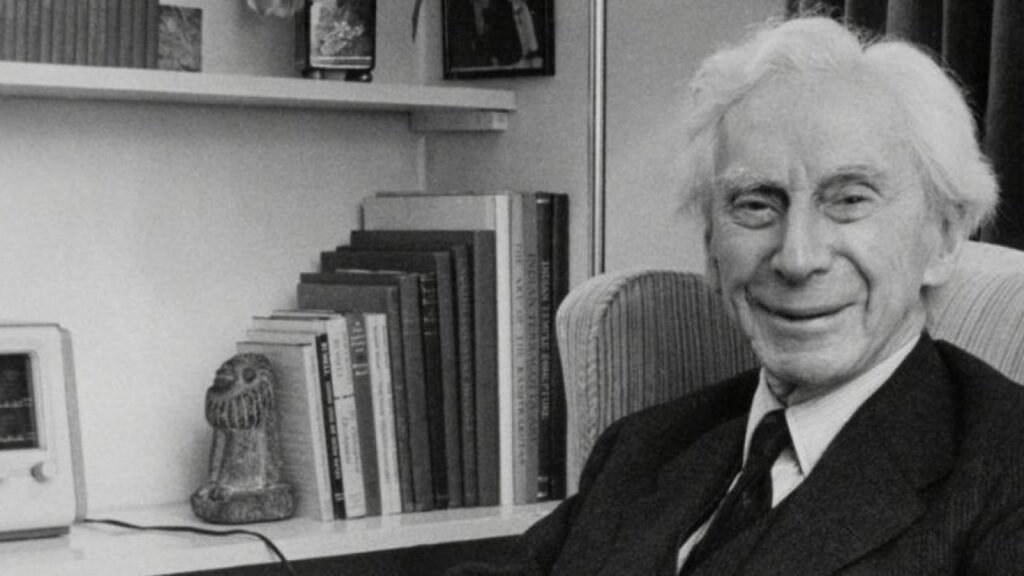

One of history’s clearest yet most brilliant thinkers, Bertrand Russell (May 18, 1872 – February 2, 1970) is remembered for his ideas that straddle timelessness and prophecy. Russell warned against its dangerous effects and defended the importance of boredom and stillness in our quest for happiness more than a century before our current age of distraction and restless productivity. His ten teaching commandments are still among the best-articulated principles of education ever. His understanding of human nature sheds light on everything from our propensity for violence to our yearning for grace. Russell’s catalog of credos from 1925, What I Believe (public library), a sort of moral ecology that also gave us Russell’s on immortality and the purpose of religion, is where his blazing brilliance warms the mind and spirit the most.

After defining the good life, Russell writes: “The good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge.” The more important of these two ingredients, the one humanity has spent centuries trying to define and entire philosophies to master is the one he turns to: “Neither love without knowledge, nor knowledge without love can produce a good life.” Russel claims:

Both love and knowledge are essential, but love is in a way more fundamental because it will motivate intelligent people to pursue knowledge in order to learn how to help the people they care about. However, if people lack intelligence, they will be content to accept what they are told and may cause harm despite the most sincere good intentions.

The great Zen master Thich Nhat Hanhs would many years later write that “to love without knowing how to love wounds the person we love.” However, Russell is careful to point out that learning how to love first necessitates that we become familiar with love’s many dimensions.

I purposefully used the word “love” because it encompasses a wide range of emotions and I want to include them all. Since love “on principle” doesn’t seem to be sincere to me, I’m just speaking about love as an emotion, which oscillates between two extremes: pure contemplative joy on the one side and pure altruistic desire on the other. We cannot feel kindness toward a landscape or a sonata; only pleasure can be felt for inanimate items. Art is probably the result of this kind of enjoyment. When compared to adults, who tend to evaluate things in a purely utilitarian way, it is typically stronger in very young children. It significantly influences how we feel about people, some of whom have charm and others the opposite when viewed only as objects of aesthetic thought.

Russell contends that the fusion of these two aspects of pleasure and goodness when gazing upon the beloved is the alchemy of complete love.

At its best, love is an unbreakable fusion of two components: joy and goodwill. Both aspects are combined in the joy a parent feels upon having a lovely, successful child, and in the best sex relationships. But in sex love, goodness can only exist where there is safe possession; otherwise, envy will destroy it, possibly even enhancing the pleasure in the thought. Without well-wishing, joy can be cruel; without joy, well-wishing can quickly turn icy and a touch arrogant. Anyone who wants to be loved wants to be the object of a love that includes both qualities.

Susan Sontag may have been troubled by the imbalance between the two as she thought about “love, sex, and the universe half a century later” Russell believes that knowledge—the second component of the ideal life—is inextricably linked to this two-legged love. He is cautious to point out that this knowledge is scientific rather than moral, that it is a knowledge of the universe in all its complete facts and shining reality. He contends that morality is a very distinct subject, but oddly, it also comes back to the same psychological drive that we have grown to equate with love: desire. He writes in a manner that suggests the juncture between Should and Must.

All moral laws must be put to the test by looking at how likely it is that they will lead to the outcomes we desire. I say goals that we want to achieve, not goals that we should aim for. What we “ought” to want is simply what other people want us to want. Typically, it is what our parents, teachers, police officers, and judges want us to want. If you tell me, “You should do so-and-so,” the motivation behind your statement is my desire for your acceptance, together with any potential benefits or penalties associated with your approval or disapproval. Since desire is the root of all conduct, it is obvious that ethical principles can only be significant insofar as they affect desire. They accomplish this by acting out of a need for acceptance and a fear of rejection. These are strong social forces, and if we want to achieve any social goals, we will naturally try to win them over to our cause.

The power of desire, according to Russell, is such that it cannot be curbed by legislation or managed through any other sticks-and-carrots system but only by being tamed and nurtured.

Making someone do something they do not want to do is not possible. It is possible to change their wants through a system of rewards and penalties, with social acceptance and rejection among the strong ones. Therefore, the question for the legislative moralist is: How should this system of incentives and penalties be set up in order to achieve the greatest amount of what the legislative power desires? There is no moral code that exists apart from human impulses.

Thus, desire rather than any specific understanding is what separates ethics from science. And yet, according to Russell, our idea of morality appears to be entirely disconnected from the truths of the human experience.

Since superstition is the source of moral principles, current morality is an odd fusion of utilitarianism and superstition, with the superstitious component holding a stronger sway. Due to the possibility that the community as a whole, rather than just the guilty individuals, would be subject to divine wrath, some actions were first considered to be detestable to the gods and were therefore prohibited by law. Thus, the idea that sin is something that offends God emerged. There is no explanation for why such actions should be so offensive.

This naturally brings to mind both Mark Twain’s broad complaint about how we have exploited religion to excuse injustice and the specific superstition that has historically surrounded homosexuality. But even in 1925, Russell, a diligent atheist, pointed out the ridiculousness of such reasoning and emphasized the need for independent thought when assessing the purported risks of what such superstition labels as “immoral.”

It is clear that a guy with a scientific outlook on life cannot allow himself to be frightened by biblical passages or church doctrine. He will ask whether the act itself causes any harm or, on the contrary, whether the belief that it is sinful causes harm. He will not be satisfied to say, “Such-and-such an act is sinful, and that ends the matter.” And he will discover that a significant portion of our existing morality, particularly when it comes to sex, has essentially superstitious roots. He will discover that this superstition, like that of the Aztecs, is motivated by unwarranted brutality and would be eliminated if people had a heart of kindness for their neighbors. However, those who uphold traditional morality are rarely kindhearted individuals. One is tempted to believe that their devotion to morals serves as a justification for their desire to hurt others; since the sinner is fair game, tolerance is out the window.

How amazing that Russell’s warning came nearly a century before DOMA was defeated and two decades before those same cruel defenders of so-called morality pushed computer pioneer Alan Turing, one of humanity’s most brilliant and significant minds, into the grave. Russell specifically tackles this issue: “Sex is one of those domains — like religion and politics — where otherwise nice and rational individuals may have powerful, irrational sentiments,” Oliver Sacks wrote in his moving autobiography many decades later.

It should be understood that when there are no children present, sexual encounters are totally private affairs that don’t affect the State or the neighbors. Currently, certain types of intercourse that do not result in offspring are punishable by law; nevertheless, this is simply superstitious because it only affects the parties directly involved.

He contends that much of this is the responsibility of education, which is at least as urgent now because creationism, the most widespread form of superstition, is still being taught in schools.

Superstition has a devastating impact on education at all levels. One of education’s goals is to break children of the habit of thinking, which a certain percentage of kids have. Questions that are uncomfortable are either ignored or punished.

Italo Calvino did not advocate for abortion rights until 50 years after The Little Red Schoolbook, but Russell skillfully exposes the misogynistic “morality” of the church.

The components of non-superstitious sexual morality should be taught during puberty. It is important to instill in both boys and girls the idea that only mutual inclination may legitimize sexual activity. Contrary to what the Church teaches, sexual activity is acceptable as long as the couple is married and the guy wants another kid, no matter how reluctant the wife may be. Both boys and girls should learn to appreciate each other’s freedom and to understand that no one has any special rights over another person and that feelings of jealousy and possessiveness are the enemies of true love. They ought to learn that giving birth is a very serious decision that should only be made when the child has a decent chance of health, a comfortable environment, and parental care. But in order to ensure that children only arrive when desired, they should also be taught birth control measures.

Russell, who wrote about the connection between morality and the two pillars of the good life decades before Martin Luther King Jr. famously declared that “injustice everywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” writes:

“Moral requirements shouldn’t be such that they prevent people from feeling instinctively happy. From beginning to end, What I Believe is a timeless gold mine of knowledge.”

We stated that the excellent life is one that is motivated by love and steered by knowledge; nonetheless, the universe is a unity, and a man who pretends to live freely is either a conscious or unconscious parasite.

A man needs to have a good education, friends, love, and children (if he wants them) in order to live a full life. He also needs to be in good health, has interesting work, and have enough money to avoid starvation and severe anxiety. All of these depend to varied degrees on the neighborhood and are aided or hindered by political developments. A good society is necessary for living the good life, and it is impossible to do so otherwise.