“Art is long and life is short, and success is very far off.”

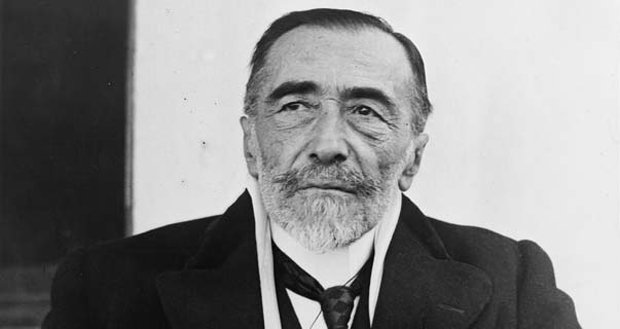

Joseph Conrad, who lived from December 3, 1857, to August 3, 1924, is best known for writing Heart of Darkness, a book that is required reading for English classes in high schools. However, much of his writing has a profoundly philosophical quality, delving into the depths of psychology, morality, the creative impulse, and other pillars of existence. A beautiful and moving addition to history’s greatest definitions of art is found in the preface to his era-appropriately inappropriately titled 1897 novella The Nigger of the “Narcissus”: A Tale of the Sea. It makes a wonderful companion to Susan Sontag’s illustrated insights on art from last week.

Conrad claims:

“A work that strives for the status of art should justify itself in every sentence, no matter how modestly. And art itself can be described as a focused effort to reveal the truth, many and one, that lies beneath every part of the visible universe in order to do it the highest sort of justice. It is an effort to discover what is fundamental, timeless, and important to each of its forms, colors, lights, shadows, features of matter, and truths of life — their one enlightening and persuading quality, the very truth of their existence. Therefore, the artist seeks the truth and makes his appeal, just like the thinker or the scientist. Inspired by the way the world is, the thinker dives into concepts, and the scientist dives into facts; from these, they now emerge and appeal to the aspects of our being that best suit us for the risky endeavor of living. They speak authoritatively to our intelligence, common sense, and desires for peace or unrest. They also frequently speak to our prejudices, fears, and egoism, but always to our credulity. And their words are listened to with respect because they deal with serious issues like the development of our thoughts and correct care of our bodies, the accomplishment of our goals, the improvement of the tools, and the exaltation of our priceless objectives.”

It is otherwise with the artist.

When faced with the same perplexing sight, the artist goes deep inside himself, where, if he is deserving and fortunate, he finds the conditions of his appeal. His appeal is made to our less evident abilities: to that aspect of our character that must be concealed behind the more resolute and hard traits due to the combative conditions of existence, like the weak body inside steel armor. His appeal is more impassioned but less loud, more profound, less clear, and more quickly forgotten. However, its impact lasts forever. The evolving wisdom of subsequent generations rejects ideas, challenges facts, and dismantles theories. However, the artist appeals to that aspect of us that is independent of wisdom; that aspect of us that is a gift rather than an acquired — and is, therefore, more enduringly long-lasting. He speaks to our capacity for wonder and awe, to the sense of mystery that surrounds our lives, to our sense of pity, beauty, and pain, as well as to the latent feeling of fellowship with all creation. He also speaks to the subtle but unbreakable conviction of solidarity that knits together the loneliness of countless hearts, as well as the solidarity in dreams, joy, sorrow, aspirations, illusions, hope, and fear that binds men to one another and that unites all of humanity.

In essence, Conrad’s portrayal lands between Henry Miller’s and Neil deGrasse Tyson’s depictions of the artist and scientist, respectively. Conrad continues by adding a wise perspective to previous well-known reflections on reality versus fiction, praising music as the best form of art, much like Susan Sontag:

“Fiction appeals to temperament if it ever aspires to be considered art. In actuality, it must be, like painting, music, and all other forms of art, the allure of one temperament to all the other infinite temperaments, whose subtle and resistless power gives passing events their true significance and produces the moral and emotional atmosphere of the place and time. Since temperament, whether it be individual or communal, cannot be persuaded, such an appeal must be an impression communicated through the senses in order to be effective. Therefore, all art appeals first to the senses, and the artistic goal when expressing itself through written words must likewise make its appeal through the senses if its high purpose is to reach the hidden spring of responsive emotions. It must ardently strive for the magic suggestiveness of music, the fluidity of sculpture, and the color of painting — which is the art of arts. And only through a total, unwavering dedication to the ideal fusion of form and substance; only through an unrelenting, never-discouraged concern for the shape and ring of sentences can an approach be made to plasticity, to color, and that the light of magic suggestiveness may be brought to play for an ephemeral instant over the commonplace surface of words: of the old, old words, worn thin, defaced by ages of careless usage.”

The only legitimate reason for the worker in prose is a true effort to complete that creative activity, to travel as far along that path as his strength will allow him to, and to remain unafraid of faltering, exhaustion, or censure. If a person’s conscience is clear, their request to be edified, comforted, or amused; or their request to be immediately encouraged; frightened; shocked; or charmed; must be met with the following response: “My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear; it is, before all else, to make you feel.” That is all there is, nothing more, nothing else. If I am successful, you will find there everything you need: inspiration, solace, fear, charm — everything you need — and perhaps even that glimmer of reality you neglected to ask for.

Conrad addresses the loyalty and sincerity that unite great art’s audience:

“The challenge doesn’t end with snatching a moment of bravery from the merciless flow of time, a fleeting stage of existence. The aim is to steadfastly hold up the salvaged fragment in front of everyone in the light of a real mood, without hesitation, without choice, and without fear. Its purpose is to demonstrate its motion, color, and form while revealing the essence of the truth—its motivating secret—which is the tension and fervor at the heart of every persuasive moment. If one makes a focused effort of that nature and is deserving and fortunate, one might eventually reach a level of sincerity that awakens in the hearts of the beholders the sense of unavoidable solidarity—the solidarity in mysterious origin, in labor, in joy, in hope, in uncertain fate, which binds men to one another and all of humanity to the visible world.”

Conrad ends with a lovely metaphor that sums up art as both a construct and a context:

“We occasionally observe the movements of a worker in a distant field while stretched out in the comfort of a roadside tree. After a while, we start to languidly wonder what the person may be doing. We observe his bodily movements and arm motions as he bends down, stands up, pauses, and then starts over. Knowing the objective of his efforts may enhance the attractiveness of an idle hour. If we are aware that he is attempting to lift a stone, dig a ditch, or uproot a stump, we are more likely to be interested in his efforts; we are also more likely to excuse the disturbance his agitation has caused to the tranquility of the surroundings; and, if we are in a brotherly mood, we may even be able to forgive his failure. We recognized his goal, and even if he made an effort, perhaps he lacked the necessary strength or wisdom. We forget after we have forgiven and moved on.”

The same is true for the artist’s work. Success is far away, life is short, and art is long. As a result, we briefly discuss the goal of art, which is motivating, challenging, and shrouded in clouds, doubting our ability to travel so far. It is not in the unmistakable logic of a victorious conclusion, nor is it in the discovery of one of those cold-blooded mysteries known as the Laws of Nature. It is only more difficult, not less great.

To make people pause for a look, a sigh, or a smile is the goal, which is difficult and fleeting and only a few are able to accomplish it. Men who are enthralled by the sight of distant goals are forced to look away for a moment and take in the surrounding vision of form and color, sunshine, and shadows. But occasionally, by the fortunate and deserving, even that effort is completed. A moment of vision, a sigh, a smile, and the return to an eternal rest are all there when it is completed, as you can see.