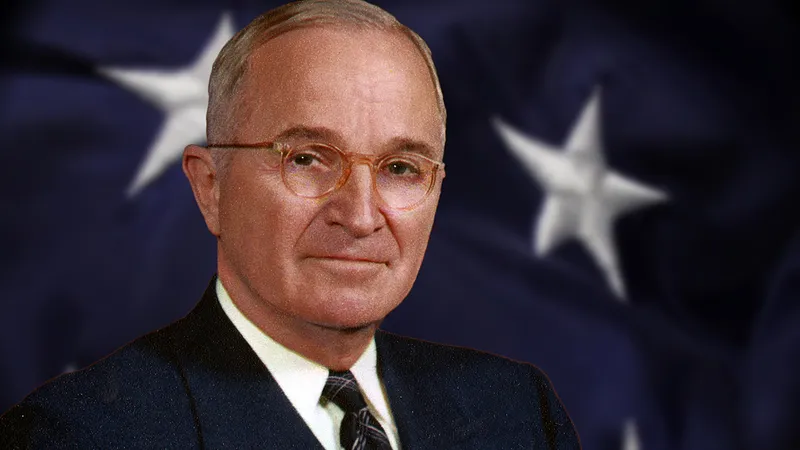

The “Truman Doctrine” of March 1947, which mirrored President Harry Truman’s combativeness, was the first stage that enhanced the influence of the United States in the eyes of the world. Congress was to be “scared to hell” by Truman.

Truman rejected the isolation policy of the US after World War 2. He argued that without assistance from friendly countries, Greece and Turkey could become targets of subversion. He asked Congress to approve $400 million in emergency aid. “I believe we must assist free peoples to sort out their futures in their own way,” he remarked to support this course of action. Attacking the conditions of “misery and want” that bred totalitarianism was essential to averting the fall of free states.

Soon, the entirety of Western Europe was subject to this basic norm. The extension of significant economic aid to the devastated nations of Europe was proposed by Secretary George C. Marshall in June 1947. He claimed that the United States foreign policy was not directed “against any country or doctrine, but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos.”

The restoration of a robust global economy ought to be its goal in order to create the political and social environment necessary for the existence of free institutions. The U.S. plan was to open to the Soviet Union and its satellites in Eastern Europe, but the Secretary of State omitted to mention that it highlighted the free market economy as the greatest route to economic reconstruction and the best bulwark against communism in Western Europe.

In response to Marshall’s proposal, Congress approved the Marshall Plan, also known as the European Recovery Program. A roughly $13 billion investment in Europe over the following few years led to the very quick and robust reconstruction of a democratic Western Europe.