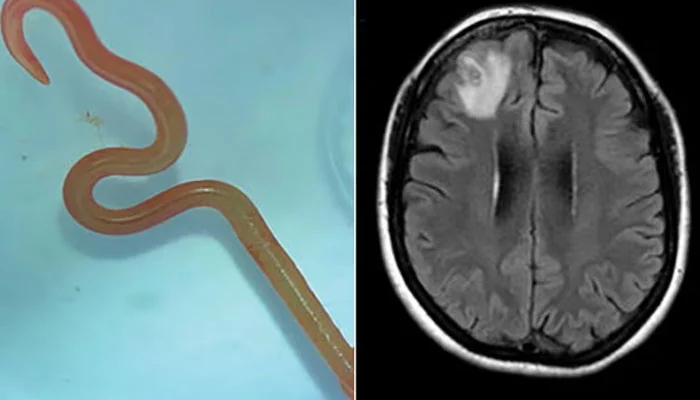

8cm python roundword pulled out from woman’s brain.

A live snake roundworm has been extracted from a woman’s brain, which has stunned the medical community.

The 64-year-old patient from south-eastern New South Wales underwent a complex surgery at Canberra Hospital that resulted in the shocking discovery.

Dr. Hari Priya Bandi, the neurosurgeon who performed the treatment, was taken aback when she extracted an 8cm-long parasitic roundworm from the patient’s brain.

The unexpected incident was discovered by the doctor during an operation to treat the patient’s symptoms, which included abdominal pain, fever, and neurological abnormalities.

Dr Bandi immediately sought advice from her medical colleagues, including infectious diseases specialist Dr Sanjaya Senanayake.

8cm python roundword pulled out from woman’s brain, Watch the video:

Dr Senanayake expressed his shock, saying, “Neurosurgeons regularly deal with infections in the brain, but this was a once-in-a-career finding. No one was expecting to find that.”

The medical staff at Canberra Hospital quickly banded together to determine the identify of the roundworm and choose the best course of action for the patient.

As the team combed through medical literature and resources, they were unable to find a similar case.

Also read: Watch: 19 Foot longest-ever Burmese Python caught in US

They sought expert advice from a CSIRO scientist with special expertise of parasites.

The expert recognised the living worm as the Ophidascaris robertsi roundworm, which is typically found in pythons.

Surprisingly, this was the first time this parasite had been detected in people.

The patient’s possible method of infection has generated some intriguing suggestions.

While she had no direct interaction with snakes, she was in an area populated by carpet pythons.

The patient may have been exposed to the parasite indirectly by contaminated grasses she used in her cooking.

“She often collected native grasses, including warrigal greens, from around the lake to use in cooking,” Dr Senanayake said.

The case’s distinctiveness necessitated cautious and measured medical intervention.

The patient’s treatment includes addressing the possibility of larvae in other places of her body.

However, because the medical team was inexperienced with this particular disease, they had to proceed carefully.

Inflammation caused by dying larvae could be dangerous, especially in delicate tissues such as the brain.

As a result, a comprehensive approach was taken to assure the patient’s safety.

Dr. Senanayake praised the patient’s bravery, recognising the significance of being the first person in the world to confront such a predicament.

Researchers are investigating the potential of a pre-existing medical condition that may have contributed to the parasite’s penetration as the patient continues to recuperate under close surveillance.

This extraordinary instance, reported in the journal Emerging Infectious illnesses, highlights the dangers of zoonotic illnesses, in which pathogens spread from animals to humans.

Dr Senanayake emphasised the broader implications, saying, “This Ophidascaris infection does not transmit between people, so this patient’s case won’t cause a pandemic like Covid-19 or Ebola.”

As habitats intertwine, the risk of novel infections necessitates increased vigilance, he concluded.