I grew up around Heeramandi!

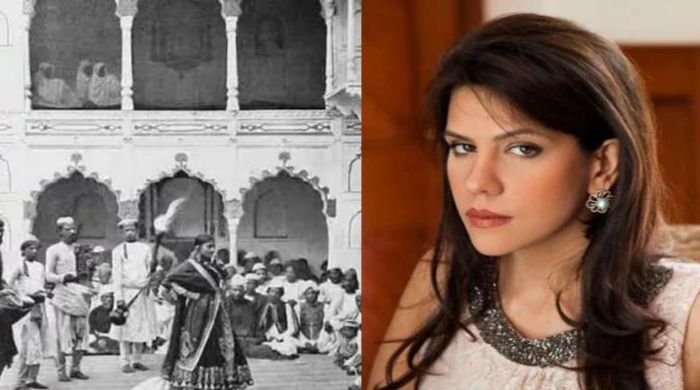

OK although I mentioned it to grab your attention, it was actually just past Heeramandi where my family’s Haveli, Barood Khana, was located. As a child, my grandmother would often take me on a Tonga ride along the narrow streets, passing the infamous market, to visit our relatives. I vividly remember seeing disheveled-looking ladies propositioning passers-by near the doorways, while the girls on the balconies above appeared more groomed and enticing. My grandmother, Christabel Belquis Taseer, explained that the higher up they were sitting , the more exclusive their business became, with the most cultured ladies hidden away in the far interiors of the Mandi.

During my pre-teen years, I developed a passion for learning the harmonium and Kathak dance. To pursue these hobbies, I would visit the Mandi to buy a harmonium and get it tuned perfectly. I also went there to purchase ghungaroos for my dance lessons. I usually went alone with a driver, secretly enjoying the forbidden and intriguing world of Heeramandi. The person selling the harmonium was a transgender individual who also acted as a broker for the young talent lingering near the doorways. With vibrant lipstick and heavy black kohl, he would encourage me, predicting that I would become a great musician one day (which never happened), and even insisted on teaching me the tabla. While selling me the harmonium, he would simultaneously conduct night deals for the dancing girls , bargaining prices and using vulgar language towards those who refused to pay generously for untouched or underage women under his commission.

My journey into the depths of Heeramandi continued when I ventured to purchase ghungaroos directly from the madams themselves. These madams were the old keepers of the houses of Tawaifs or courtesans. Deliberately, I would spend hours selecting my ghungaroos, immersing myself in the daily lives of this vibrant community. The cheap, shiny, gold-belled ghungaroos with large bells on a blood-red velvet base were made in Pakistan, while the smaller, matte gold ghungaroos with a tinkling sound, sewn onto a maroon velvet base, were prized imports from India. Obtaining the imported ones required multiple trips to Heeramandi and engaging in conversations with the madams. They would treat me to Keema nans and mixed chai in blue tin cups while ordering the ghungaroos for me. During these visits, I would listen to their woeful tales, including stories about mourning the birth of a boy and instances of girls running off with their sweethearts only to be mistreated. One madam even shared an incident where a gentleman had misbehaved with one of her girls and received a collective thrashing from all the courtesans, dalals, and then groups of Hijras were sent to his family home to expose his reprehensible actions in the Mandi.

Also read: Khabarhar’s Aftab Iqbal reviews Netflix’s Heeramandi

As a teenager growing up in Lahore, I attended some Mujras at weddings. During one of these events, the famous dancing sisters Guddi and Chanda were invited, and they captivated the late evening by gracefully falling to the floor, brushing it with their hair, and twirling amidst a shower of currency notes. I remembered Chanda a young girl then, from my ghungaroo buying days, and after her performance, we had a heart-to-heart conversation about some of her heartbreaking life experiences. This tête-à-tête surprised and upset my family members, including my father, who questioned how I had become so friendly with the likes of Madam Chanda.

Watching the serial “Heeramandi” brought back many of these memories. While it provided glimpses of the Heeramandi I knew, it unfortunately failed to capture the true essence and reality of the place which I hope some artistic director can capture some day.