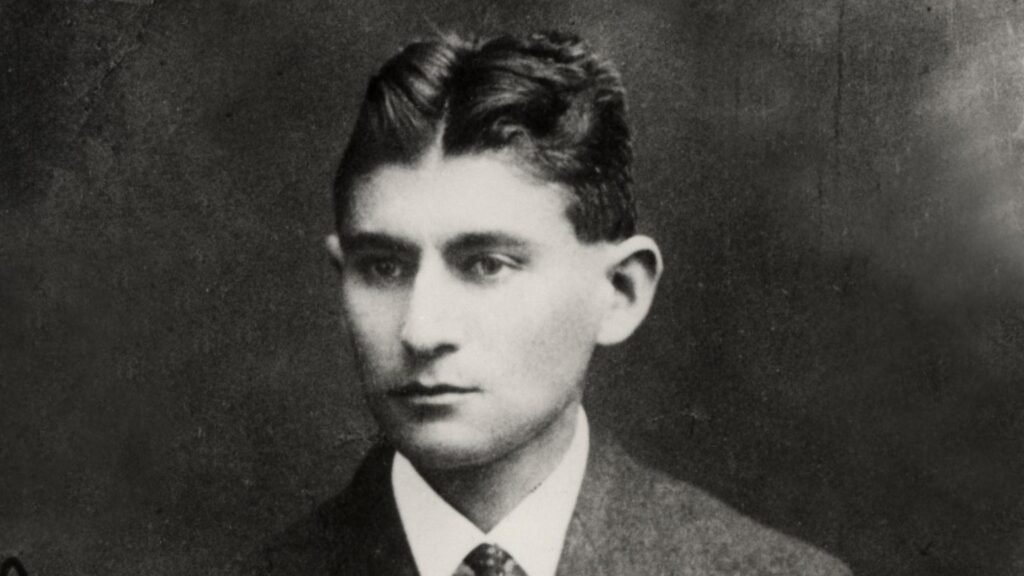

Franz Kafka was one of history’s most prolific and expressive practitioners of what Virginia Woolf called “the humane art.” Among the hundreds of epistles he penned during his short life were his beautiful and heartbreaking love letters and his magnificent missive to a childhood friend about what books do for the human soul. Although he imbued most with an extraordinary depth of introspective insight and self-revelation, none surpass the 47-page letter he wrote to his father, Hermann, in November of 1919 — the closest thing to an autobiography Kafka ever produced. A translation by Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins was posthumously published as Letter to His Father (public library) in 1966.

His litany of indictments is doubly harrowing in light of what psychologists have found in the decades since — that our early limbic contact with our parents profoundly shapes our character, laying down the wiring for emotional habits and patterns of connecting that greatly influence what we bring to all subsequent relationships in life, either expanding or contracting our capacity for “positivity resonance” depending on how nurturing or toxic those formative relationships were. For those of us with similar experiences, be it inflicted by a patriarch or a matriarch, Kafka’s letter to his father is at once excruciating in its deep resonance and strangely comforting in its validation of shared reality.

Kafka writes:

Dearest Father,

“You asked me recently why I maintain that I am afraid of you. As usual, I was unable to think of any answer to your question, partly for the very reason that I am afraid of you, and partly because an explanation of the grounds for this fear would mean going into far more details than I could even approximately keep in mind while talking. And if I now try to give you an answer in writing, it will still be very incomplete, because, even in writing, this fear and its consequences hamper me in relation to you and because the magnitude of the subject goes far beyond the scope of my memory and power of reasoning.”

Kafka paints the backdrop of his father’s emotional tyranny and lays out what he hopes the letter would accomplish for both of them:

“To you, the matter always seemed very simple, at least in so far as you talked about it in front of me, and indiscriminately in front of many other people. It looked to you more or less as follows: you have worked hard all your life, have sacrificed everything for your children, above all for me, consequently, I have lived high and handsome, have been completely at liberty to learn whatever I wanted, and have had no cause for material worries, which means worries of any kind at all. You have not expected any gratitude for this, knowing what “children’s gratitude” is like, but have expected at least some sort of obligingness, some sign of sympathy. Instead, I have always hidden from you, in my room, among my books, with crazy friends, or with extravagant ideas… If you sum up your judgment of me, the result you get is that, although you don’t charge me with anything downright improper or wicked (with the exception perhaps of my latest marriage plan), you do charge me with coldness, estrangement, and ingratitude. And, what is more, you charge me with it in such a way as to make it seem my fault, as though I might have been able, with something like a touch on the steering wheel, to make everything quite different, while you aren’t in the slightest to blame unless it is for having been too good to me.

This, your usual way of representing it, I regard as accurate only in so far as I too believe you are entirely blameless in the matter of our estrangement. But I am equally entirely blameless. If I could get you to acknowledge this, then what would be possible is — not, I think, a new life, we are both much too old for that — but still, a kind of peace; no cessation, but still, a diminution of your unceasing reproaches.”

We were so different and in our difference so dangerous to each other that if anyone had tried to calculate in advance how I, the slowly developing child, and you, the full-grown man, would stand to each other, he could have assumed that you would simply trample me underfoot so that nothing was left of me. Well, that did not happen. Nothing alive can be calculated. But perhaps something worse happened. And in saying this I would all the time beg of you not to forget that I never, and not even for a single moment, believe any guilt to be on your side. The effect you had on me was the effect you could not help having. But you should stop considering it some particular malice on my part that I succumbed to that effect.

I was a timid child. For all that, I am sure I was also obstinate, as children are. I am sure that Mother spoilt me too, but I cannot believe I was particularly difficult to manage; I cannot believe that a kindly word, a quiet taking by the hand, a friendly look, could not have got me to do anything that was wanted of me. Now you are, after all, at the bottom a kindly and softhearted person (what follows will not be in contradiction to this, I am speaking only of the impression you made on the child), but not every child has the endurance and fearlessness to go on searching until it comes to the kindliness that lies beneath the surface. You can only treat a child in the way you yourself are constituted, with vigor, noise, and hot temper, and in this case, this seemed to you, into the bargain, extremely suitable, because you wanted to bring me up to be a strong brave boy.

I was quite obedient afterward at that period, but it did me inner harm. What was for me a matter of course, that senseless asking for water and the extraordinary terror of being carried outside were two things that I, my nature being what it was, could never properly connect with each other. Even years afterward I suffered from the tormenting fancy that the huge man, my father, the ultimate authority, would come almost for no reason at all and take me out of bed in the night and carry me out onto the [balcony], and that meant I was a mere nothing for him.

What I would have needed was a little encouragement, a little friendliness, a little keeping open of my road, instead of which you blocked it for me, though of course with the good intention of making me go another road. But I was not fit for that… At that time, and at that time in every way, I would have needed encouragement.

You had worked your way so far up by your own energies alone, and as a result, you had unbounded confidence in your opinion. That was not yet so dazzling for me as a child as later for the boy growing up. From your armchair, you ruled the world. Your opinion was correct, every other was mad, wild, meshugge, not normal. Your self-confidence indeed was so great that you had no need to be consistent at all and yet never ceased to be in the right. It did sometimes happen that you had no opinion whatsoever about a matter and as a result, all opinions that were at all possible with respect to the matter were necessarily wrong, without exception. You were capable, for instance, of running down the Czechs, and then the Germans, and then the Jews, and what is more, not only selectively but in every respect, and finally nobody was left except yourself. For me, you took on the enigmatic quality that all tyrants have whose rights are based on their person and not on reason.

All these thoughts, seemingly independent of you, were from the beginning burdened with your belittling judgments; it was almost impossible to endure this and still work out a thought with any measure of completeness and permanence.

It was only necessary to be happy about something or other, to be filled with the thought of it, to come home and speak of it, and the answer was an ironical sigh, a shaking of the head, a tapping on the table with a finger… Of course, you couldn’t be expected to be enthusiastic about every childish triviality, when you were in a state of fret and worry. But that was not the point. Rather, by virtue of your antagonistic nature, you could not help but always and inevitably cause the child such disappointments; and further, this antagonism, accumulating material, was constantly intensified; eventually, the pattern expressed itself even if, for once, you were of the same opinion as I; finally, these disappointments of the child were not the ordinary disappointments of life but, since they involved you, the all-important personage, they struck to the very core. Courage, resolution, confidence, delight in this and that, could not last when you were against it or even if your opposition was mere to be assumed; and it was to be assumed in almost everything I did.

What was always incomprehensible to me was your total lack of feeling for the suffering and shame you could inflict on me with your words and judgments. It was as though you had no notion of your power. I too, I am sure, often hurt you with what I said, but then I always knew, and it pained me, but I could not control myself, could not keep the words back, I was sorry even while I was saying them. But you struck out with your words without much ado, you weren’t sorry for anyone, either during or afterward, one was utterly defenseless against you.

The main thing was that the bread should be cut straight. But it didn’t matter that you did it with a knife dripping with gravy. Care had to be taken so that no scraps fell on the floor. In the end, it was under your chair that there were most scraps.

Since there was nothing at all I was certain of since I needed to be provided at every instant with a new confirmation of my existence since nothing was in my very own, undoubted, sole possession, determined unequivocally only by me — in sober truth a disinherited son — naturally, I became unsure even of the thing nearest to me, my own body.

Please, Father, understand me correctly: in themselves, these would have been utterly insignificant details, they only became depressing for me because you, so tremendously the authoritative man, did not keep the commandments you imposed on me. Hence the world was for me divided into three parts: one in which I, the slave, lived under laws that had been invented only for me and which I could, I did not know why, never completely comply with; then a second world, which was infinitely remote from mine, in which you lived, concerned with government, with the issuing of orders and with the annoyance about there not being obeyed; and finally a third world where everybody else lived happily and free from orders and from having to obey. I was continually in disgrace; either I obeyed your orders, and that was a disgrace, for they applied, after all, only to me; or I was defiant, and that was a disgrace too, for how could I presume to defy you; or I could not obey because I did not, for instance, have your strength, your appetite, your skill, although you expected it of me as a matter of course; this was the greatest disgrace of all.

[Your] frightful, hoarse undertone of anger and utter condemnation … only makes me tremble less today than in my childhood because the child’s exclusive sense of guilt has been partly replaced by insight into our helplessness, yours and mine.

The impossibility of getting on calmly together had one more result, actually a very natural one: I lost the capacity to talk. I dare say I would not have become a very eloquent person in any case, but I would, after all, have acquired the usual fluency of human language. But at a very early stage, you forbade me to speak. Your threat, “Not a word of contradiction!” and the raised hand that accompanied it has been with me ever since. What I got from you — and you are, whenever it is a matter of your own affairs, an excellent talker — was a hesitant, stammering mode of speech, and even that was still too much for you, and finally, I kept silent, at first perhaps out of defiance, and then because I could neither think nor speak in your presence. And because you were the person who really brought me up, this has had its repercussions throughout my life.

[…]

Your extremely effective rhetorical methods in bringing me up, which never failed to work with me, were: abuse, threats, irony, spiteful laughter, and — oddly enough — self-pity.

I cannot recall your ever having abused me directly and in downright abusive terms. Nor was that necessary; you had so many other methods, and besides, in a talk at home and particularly at business the words of abuse went flying around me in such swarms, as they were flung at other people’s heads, that as a little boy, I was sometimes almost stunned and had no reason not to apply them to myself too, for the people you were abusing were certainly no worse than I was and you were certainly not more displeased with them than with me. And here again, was your enigmatic innocence and inviolability; you cursed and swore without the slightest scruple, yet you condemned cursing and swearing in other people and would not have it.

One had, so it seemed to the child, remained alive through your mercy and bore one’s life henceforth as an undeserved gift from you.

[…]

It is also true that you hardly ever really gave me a whipping. But the shouting, the way your face got red, the hasty undoing of the braces and laying them ready over the back of the chair, all that was almost worse for me. It is as if someone is going to be hanged. If he really is hanged, then he is dead and it is all over. But if he has to go through all the preliminaries to being hanged and he learns of his reprieve only when the noose is dangling before his face, he may suffer from it all his life. Besides, from the many occasions on which I had, according to your clearly expressed opinion, deserved a whipping but was let off at the last moment by your grace, I again accumulated only a huge sense of guilt. On every side I was to blame, I was in your debt.

Fortunately, there were exceptions to all this, mostly when you suffered in silence, and affection and kindliness by their own strength overcame all obstacles and moved me immediately. Rare as this was, it was wonderful. For instance, in earlier years, in hot summers, when you were tired after lunch, I saw you having a nap at the office, your elbow on the desk; or you joined us in the country, in the summer holidays, on Sundays, worn out from work; or the time Mother was gravely ill and you stood holding on to the bookcase, shaking with sobs; or when, during my last illness, you came tiptoeing to Ottla’s room to see me, stopping in the doorway, craning your neck to see me, and out of consideration only waved to me with your hand. At such times one would lie back and weep for happiness, and one weep again now, writing it down.

It is true that Mother was illimitably good to me, but for me all that was in relation to you, that is to say, in no good relation. Mother unconsciously played the part of a beater during a hunt. Even if your method of upbringing might in some unlikely case have set me on my own feet by means of producing defiance, dislike, or even hate in me, Mother canceled that out again by kindness, by talking sensibly (in the maze and chaos of my childhood she was the very prototype of good sense and reasonableness), by pleading for me; and I was again driven back into your orbit, which I might perhaps otherwise have broken out of, to your advantage and to my own.

[…]

If I was to escape from you, I had to escape from the family as well, even from Mother. True, one could always get protection from her, but only in relation to you. She loved you too much and was too devoted and loyal to you to have been for long an independent spiritual force in the child’s struggle.

Relations with people outside the family … suffered possibly still more under your influence. You are entirely mistaken if you believe I do everything for other people out of affection and loyalty, and for you and the family nothing, out of coldness and betrayal. I repeat for the tenth time: even in other circumstances I should probably have become a shy and nervous person, but it is a long dark road from there to where I have really come.

[In my writing] I had, in fact, got some distance away from you by my own efforts, even if it was slightly reminiscent of the worm that, when a foot treads on its tail end, breaks loose with its front part and drags itself aside. To a certain extent I was in safety; there was a chance to breathe freely. The aversion you naturally and immediately took to my writing was, for once, welcome to me. My vanity, my ambition did suffer under your soon proverbial way of hailing the arrival of my books: “Put it on my bedside table!” (usually you were playing cards when a book came)… My writing was all about you; all I did there, after all, was to bemoan what I could not bemoan upon your breast. It was an intentionally long-drawn-out leave-taking from you, yet, although it was enforced by you, it did take its course in the direction determined by me.

In my writing, and in everything connected with it, I have made some attempts at independence, attempts at escape, with the very smallest of success; they will scarcely lead any farther; much confirms this for me. Nevertheless, it is my duty or, rather, the essence of my life, to watch over them, to let no danger that I can avert, indeed no possibility of such a danger, approach them.

Often in my mind’s eye, I saw the terrible assembly of the teachers … as they would meet, when I had passed the first class, and then in the second class, when I had passed that, and then in the third, and so on, meeting in order to examine this unique, outrageous case, to discover how I, the most incapable and, in any case, the most ignorant of all, had succeeded in creeping up so far as this class, which now, when everybody’s attention had at last been focused on me, would of course instantly spew me out, to the jubilation of all the righteous liberated from this nightmare. To live with such fantasies is not easy for a child.

It is, after all, not necessary to fly right into the middle of the sun, but it is necessary to crawl to a clean little spot on earth where the sun sometimes shines and one can warm oneself a little.

Things cannot in reality fit together the way the evidence does in my letter; life is more than a Chinese puzzle. But with the correction made by this rejoinder — a correction I neither can nor will elaborate in detail — in my opinion something has been achieved that so closely approximates the truth that it might reassure us both a little and make our living and our dying easier.

In life things don’t fit together as neatly as the proofs in my letter — life is more than a game of patience. But after allowing for this answer, which I can’t and don’t want to elaborate on now, I still believe my letter contains some truth, it takes us closer to the truth, and therefore it may allow us to live and die with a gentler and lighter spirit.”