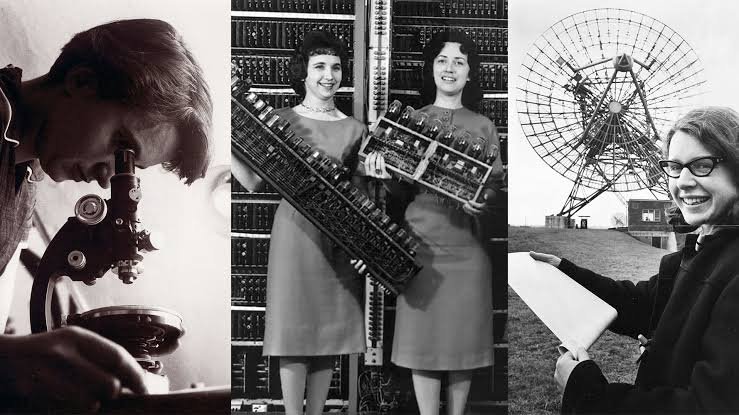

Throughout history, women have often been sidelined, either due to peer pressure, lack of opportunity, or flat-out sexism. And many times, women who invented items from disposable diapers to Monopoly weren’t given credit for their work.

Women are responsible for early sketches of the computer, the discovery of the DNA double helix, and even splitting the atom. But men claimed those advancements as their own.

Here is the Part-I of 7 things you didn’t know were invented by women.

Monopoly

Monopoly was in reality invented by Elizabeth Magie Phillips as, ironically, a protest against the monopoly of men.

America’s favorite board game was created by Elizabeth Magie Phillips. She called it “The Landlord’s Game,” and it aimed to both demonstrate the benefits of Henry George’s system of land-grabbing economics and protest monopolists of the time, like John D. Rockefeller.

Phillips filed for a patent in 1903, and the game began to circulate among niche communities but right as it was catching on, Charles Durow stepped in and secured a copyright for his own “enhanced” version, called Monopoly, which featured a few variations that made it easier to play. Durow then sold his game to Parker Brothers, and Phillips was largely lost to history.

Dark Matter

Vera Rubin made lots of progress in the field of “dark matter,” but was never really credited. Astrophysicist Vera Rubin worked with fellow researcher Kent Ford in the ’60s and ’70s. Together, they studied galaxies and wondered why things like stars were able to move so rapidly without falling apart.

Rubin’s calculations led her to surmise that there was an invisible force at play called “dark matter” — an idea first proposed by Fritz Zwicky in the 1930s. Fellow astronomers were initially reluctant to accept her theory, but soon physicists like Jeremiah Ostriker and James Peebles provided a further framework, which cemented dark matter’s place in science.

The evidence Rubin gathered was extraordinary, and ushered in “a Copernican-scale change in cosmological theory,” according to The New York Times. But Rubin never received a Nobel Prize.

The Modern Bra

The Modern Bra was in reality crafted by socialite Caresse Crosby in the early 1900s but quickly sold to a larger company.

A rebellious debutante, Caresse Crosby was just 19 when she got so angry at her corset while getting ready for a ball, she called her maid for new materials including silk handkerchiefs, cord, ribbons, and a needle and thread. She sewed what we now know as a bra on the spot.

In 1914, Crosby was able to patent her invention, which she called the “backless brassiere” and start the Fashion Form Brassiere Company in Boston.

But she soon sold her design for a mere $1,500 to the Warner Brothers Corset Company, which detached her name from its history. Warner would go on to make $15 million off Crosby’s invention over the next 30 years.

Who Disprove Law of Parity

Nuclear physicist Chien-Shiung Wu lost out on a Nobel prize because two of her (male) contemporaries took credit for the work.

Held in the same esteem as Marie Curie, experimental physicist Chien-Shiung Wu worked on the Manhattan Project and she made a groundbreaking discovery in 1956.

Using radioactive cobalt, Wu conducted a series of experiments that disproved the Law of Parity. Two other researchers, Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang, had already theorized the invalidity of the Law but they needed the evidence that Wu got.

Lee and Yang were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1954, and Wu received nothing. She said on the matter, “Although I did not do research just for the prize, it still hurts me a lot that my work was overlooked for certain reasons.”

Square-bottomed paper bag

After working in a paper bag factory, inventor Margaret Knight realized that packing a bag would be easier if the bottoms were flat. So she created a working machine that formed and folded square-bottomed paper bags and helped them become mass-produced items.

As she set out to patent her invention, a man named Charles Annon stole her idea, going so far as to get a patent of his own. But Knight took it to court, and though Annon’s defense was that “no woman could invent such the innovative machine,” she ultimately won and got her patent in 1871.

DNA’s double helix

While researching at King’s College in 1951, Rosalind Franklin began taking X-Ray photographs of DNA structure.

She presented her findings — which included a shot of the double helix — at a lecture, and James Watson was in attendance. He reportedly “didn’t pay attention” during her presentation, and was later shown the photograph by Franklin’s supervisor.

Watson and Crick’s “double helix” idea was just a theory at the time, but Franklin’s photographic discovery confirmed its existence. The men published their study alongside the image in 1953.

Watson and Crick received the Nobel Prize in 1962, shortly after Franklin’s death in 1958. She never received credit for it in her lifetime.

How to Split Atoms

Austrian-Swedish physicist Lise Meitner conducted research on uranium with her lab partner, Otto Hahn.

In the early 1940s, they discovered that the act of atomic nuclei splitting during “fission” releases tremendous amounts of energy. Meitner herself wrote the first theoretical explanation of the fission process after the discovery.

But her partner, Otto Hahn, received sole credit — and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1944. Though Meitner was known as the “mother of the atomic bomb,” Hahn repeatedly defended her exclusion from the prize.