“Opinions are the most superficial things about somebody when it comes down to it.”

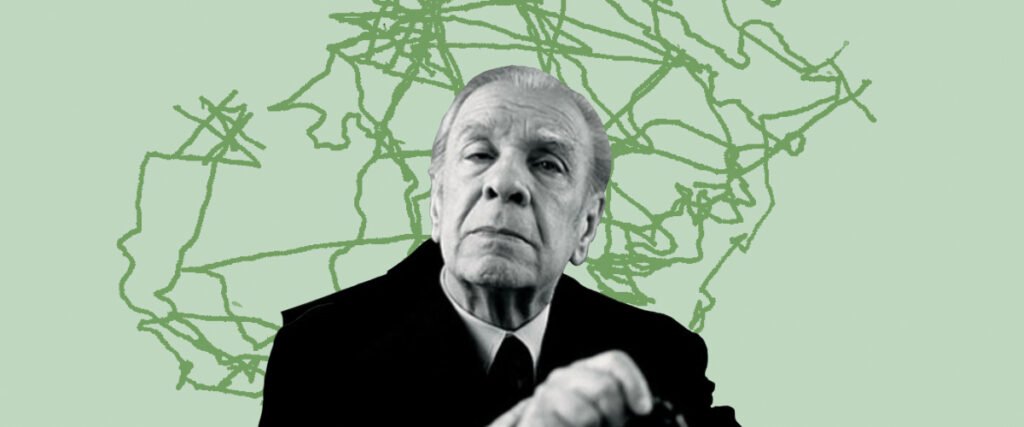

Jorge Luis Borges, who lived from August 24, 1899, to June 14, 1986, is one of literature’s most cherished and important authors. His work has influenced a vast body of literature as well as mathematical discoveries and philosophical children’s books. Susan Sontag paid him the most exquisite tribute in literary history after his passing.

Borges consented to have many chats with a young Argentine writer and a voracious reader named Fernando Sorrentino in 1972 when he was in his seventies and already totally blind. The two men met in a quiet room in the National Library of Argentina on seven afternoons and had open discussions about literature and life, despite having lived more than forty years apart. The transcript of these eye-opening meetings, which provides the most direct look into the mind of the adored author, was released in 1974 as Seven Conversations with Jorge Luis Borges, the same excellent book that offered us Borges’s timeless advice on writing.

Borges analyses the topic of success and its genuine metrics through the lens of his great artistic integrity and cultural vision in one of the most ageless yet acutely contemporary passages of the discussion. He discusses the distinction between literature and other arts when asked if he cares what readers and viewers think:

“A book might not get much attention when it is first released; it might later be found. However, in the case of a movie, the failure or success has to happen right away (and this makes everything more dramatic; let’s say the same thing happens with the dancer’s or performer’s art). I believe that the mere fact that a hall is packed with people in itself produces a unique atmosphere.”

This time scale of success seems to be shared by literature and fine art, which is very different from that of the performing and popular arts. One wonders if Borges gave his younger sister, Norah, any thought as he pondered the issue of latent recognition; while she was a hugely successful graphic artist while she was alive, it wasn’t until after her passing that she gained recognition as a modern art pioneer.

Norah Borges’s artwork. For more, click the image. He adds, keeping in mind the psychology of crowds:

“You must have noticed this quite frequently—people react more exaggeratedly when they join a group. People may laugh when someone tells a joke in front of a small group, but not in the same way that 500 or 1000 people may laugh when a joke is told in a play or a movie. That is, there is a propensity for greater exaggeration and a propensity for everything to occur emphatically. And it’s odd that when people are with other people, they tend to let loose more. A solitary reader or spectator, on the other hand, appears to react less strongly or modestly than when surrounded by others.”

The best way to truly assess a work is to read it alone. It’s a different kind of evaluation, though, in any case. Returning to the absurdity of evaluation by popular opinion, which Georgia O’Keeffe and Kierkegaard both bemoaned, Borges notes: “When it comes down to it, views are the most unimportant characteristics of anyone.”

After over 50 years of commercialism, Borges discusses how the commodity of literature has distorted its success criteria in a feeling that is triple relevant today.

It’s probable that the commercialization of literature in a way that has never been seen before has had an impact. That is the fact that “bestsellers” are discussed today and that fashion is influential (which didn’t happen before). When I first started writing, I recall that we never considered a book’s likelihood of success or failure. The concept of “success” as we know it now didn’t exist then. And what is referred to as “failure” was accepted as normal?

As Stevenson once said, one wrote for oneself and perhaps a select circle of close friends. Conversely, one now considers sales. I am aware of authors who publicly declare they have issued their fifth, sixth, or seventh edition and have made a certain sum of money. When I was a young man, all of it would have seemed completely absurd; it would have seemed unbelievable. People would have assumed that a writer who discusses his book earnings is suggesting: “I know what I write is poor but I do it for financial reasons or because I have to feed my family.” I, therefore, see that mentality as being somewhat humble. or just simple stupidity.

This echoes Borges’ earlier observation on the different epochs of literary appreciation against that of more popular arts like film and music. The idea of the “bestseller” is culturally related to the “blockbuster” and the “hit” — note how violent our laudatory language is often — but, as Borges implies and a plethora of other authors have confirmed, the success of literature is determined by a totally different metric of inner light.

The entirety of Seven Conversations with Jorge Luis Borges is a fantastic read. Add to that some more of the renowned author’s writing advice and a wonderful children’s book that was influenced by his concepts about memory, then go back to his advice on defining your own success.